Effectively communicating sustainability across sectors

What do European climate scientists, Midwest U.S. organic farmers, and small arts organizations have in common? They all have a huge amount of data (or potential for it) and battle with balancing science and more personal, emotional messages in their communications.

In the past few months, I’ve presented to scientists at the Copernicus Climate Change Service general assembly in Europe, to organic farmers at the Midwest Organic Farming Conference (MOSES), and to artists and arts organizations as a panelist at Data for Art.

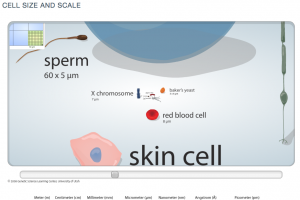

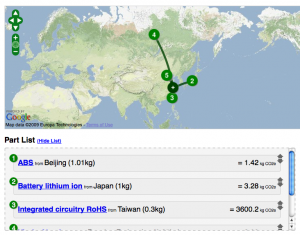

In order help audiences grasp the very complex scenarios involved in each of these industries, we have to both produce solid, objective research about these subjects and provide more subjective entry points into the information. Our goal: Help non-experts grasp the concepts and navigate the content. These entry points should show how the data can be understood from a variety of different perspectives, and aim to tell stories with the data. Visual stories reach audiences and help people connect with these complex concepts.

We have to improve how we communicate this important information, so that our audiences — policymakers, stakeholders, businesses, consumers, and citizens — can more fully engage and ultimately take action. Because if people can’t grasp the information, they default to ‘Business as Usual’: they ignore the information and do nothing (and that won’t help our planet one bit!). We can do better, and when audiences are more engaged, our organizations benefit and so does our common cause. — AB

It’s not hard to believe, given the events of the past year, to see how people do not make decisions based purely on fact. Appeals to our personal beliefs and emotional centers are important. Data alone does not influence decisions. To a large portion of society,

It’s not hard to believe, given the events of the past year, to see how people do not make decisions based purely on fact. Appeals to our personal beliefs and emotional centers are important. Data alone does not influence decisions. To a large portion of society,